“Scientific research does not establish causality in the relationship between social media usage and its effects on mental health,” stated Mark Zuckerberg of Meta this week before the U.S. Senate committee on online child safety and the role of social media therein. CEOs of X, Meta, Snap, TikTok, and Discord are being questioned and roasted regarding the measures they are taking and the tools they are developing to protect children from the negative impacts on mental health and suicide. Mark Zuckerberg even offers live apologies to the parents present whose children have been victimized.

It appears that we agree on the existence of these effects, as evidenced by the parents of victims attending these hearings. Mark Zuckerberg’s remark that causal effects are not found in science is, therefore, noteworthy.

Does Mark Zuckerberg have a valid point?

This topic was recently discussed during the University of Amsterdam lecture titled ‘Why we see media effects but do not find them.’ Suzanne Baumgartner mentioned three possible reasons why some media effects are challenging to measure. Impact on happiness, loneliness and well being are hard indeed to measure. Why don’t we find strong effects?

One reason is that the effects are generally not linear, while the statistical (regression) models commonly used in social science are. Another problem is that media are always on and widely used, so we cannot compare with a control group that wasn’t exposed to it. This makes most scientific research methods unusable.

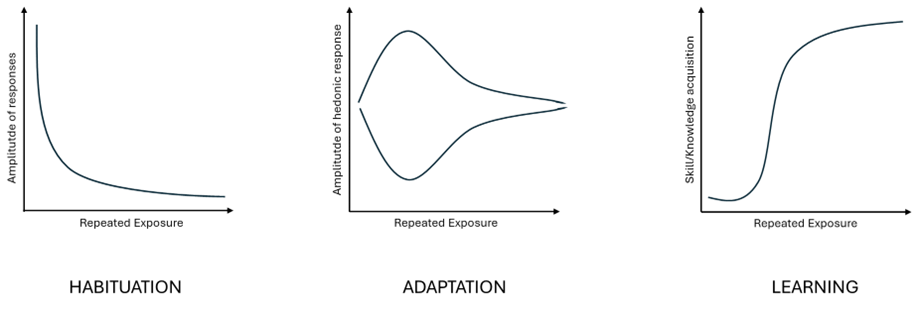

Many media effects, however, are non-linear. This is also acknowledged in media planning, where the effect diminishes as the number of exposures (frequency of exposure, as communication involves repetition) increases. With these diminishing returns curves, TV advertising campaigns are optimized for cost efficiency. Three non-linear effects were discussed that frequently occur.

Habituation effects

It is a well-known phenomenon that we ‘desensitize’ from excessive media exposure, leading to a decrease in effects. We become accustomed and num to images of hunger, pornography, and war. We call that wear-out effects in communication. The effect diminishes as exposure increases. These diminishing returns curves are also used in Marketing Mix Modeling to calculate the effects of advertising on sales, for example, which does not increase linearly.

Adaptation effects

A second effect is adaptation. A lot of the same can lead to aversion (after a month of pancakes every day, you never want pancakes again). So, repeated exposure can change how people are thinking about it and also the type of impact (from positive to negative or the other way around) can change. Social media can be great at first becoming harmful later, as learned from the hearings in the U.S. Congress last week (depression, loneliness, exploitation).

Learning effects

The learning effect shows an S-curve where the effect starts slow, than accelerates and slows down again.

Unfortunately, these effects/coping mechanisms (habituation, adaptation, and learning effects) are challenging to study in practice. Some recommendations:

- Data is lacking, and there are too few usable experiments conducted. Preferably we should not look for differences and effects between groups (between person effects) but within person effects. To measure the change in opinion on a personal level. Data collection is currently missing to enable this.

- We compare groups at the wrong time (when the effects have already flattened).

- Social Sciences need to step up the game and get more econometrics in their statistics.

So Mark Zuckerberg has a point that social sciences struggle to find causal proof regarding negative social media effects… In the meantime let’s agree that social platforms have to take massive responsible measures to fight misuse and harmful content on their platforms.